A core part of the level design in Mario Odyssey is the unordered nature of the challenges. Even with linear, primary objectives, players have the choice to go off the beaten path and do what they want. The lack of order gives the game natural layers to the challenges. Challenge layering is a game design technique that enables players of multiple skill levels to enjoy your game by being challenged at their appropriate skill level. Here’s how it works in Mario Odyssey:

- Low-skilled players can choose goals to focus on that fit in their flow zone, even if they struggle with others

- Mechanic synergy and level design enables emergent playstyles to make the game harder for high-skilled players (like speedrunning)

Choosing Your Goal

The nature of unordered challenges makes sure there’s always something to do no matter your skill level. We can also recognize that there are different types of skills, e.g., platforming vs. exploring. The compelling primary objectives in each level give players who get lost when exploring large environments something to focus on. Meanwhile, if a player is struggling with some platforming challenge, they can easily find some other moons to get to the next world.

In conjunction with four-part structure, being able to choose your challenge means that even if you leave the world because it’s too hard, the next world will teach you new mechanics that don’t need you to have mastered the previous world to learn.

What about design elements that add layers of challenge for high-skilled players? One example: every bonus room has two moons to find – the obvious goal and the hidden goal. Low-skilled players can settle for the obvious (possibly without realizing the hidden goal exists). High-skilled players will quickly find the pattern that there is always another secret moon and try their best to locate and obtain it. Classic objective-based challenge layering.

Mechanics Increasing Challenge

Rather than creating harder goals to add challenge layering for skilled players, Nintendo opted for using game mechanics to encourage different, more challenging ways to play.

Keeping high-skilled players moving fast is one core way to keep different player-types engaged. The jump mechanics enable skilled players to skip challenges to get moons quickly. If you’ve mastered the mechanics, you can zoom through the levels in a way that is more challenging (quickly timing the odd jumping mechanics and finding unique paths). Levels are designed to allow the jumping mechanics to help high-skilled players while low-skilled players can remain blissfully unaware that they could be moving faster (until they play a late-game Koopa race that intuitively teaches complex jump mechanics).

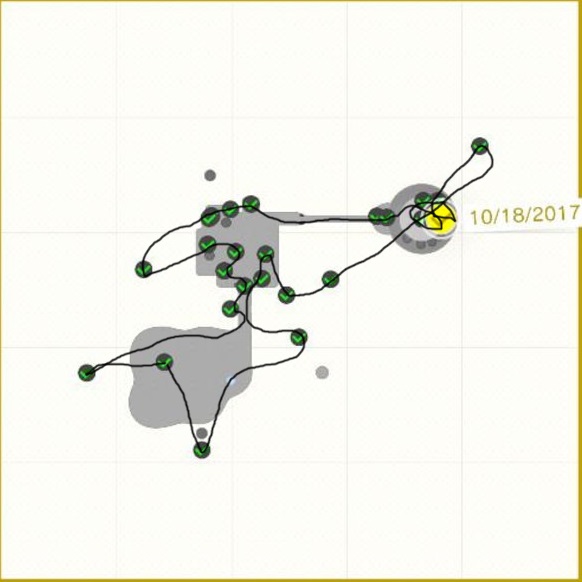

We come to the ultimate high-skilled players – the speedrunners. Unordered in-level challenges are one of the reasons why speedrunning has been so popular in this game (along with the jumping mechanics and ease of recording). Speedrunners aiming for 100% must decide which path through the level they will do. There are thousands of orders to collect the moons so for speedrunners; this is an interesting decision. Low-skilled players don’t need to worry about being optimal and have fun collecting things along their way to the main goal. Meanwhile, optimal paths are crucial for speed runners.

Look at Mario 64. When you enter a level, you have one goal to choose – the single star you’re trying to obtain. Your decisions are finding the shortest route through the level to reach your star (for the programmers, this is polynomial algorithm). But in Banjo-Kazooie or Odyssey, you have multiple goals you want, and you have to choose the order. The numerous goals make the path through the level equivalent to the traveling salesman problem – you want to find the optimal route to collect all the goals in the least amount of time (for the programmers, an NP-hard algorithm – i.e., very complex). It can be gratifying to high-skilled players to come up with what they think is the best path.

A caveat about “Challenges”

Possibly the most controversial part of Mario Odyssey. Many of these side challenges, the hundreds of moons scattered about, are criticized for being too easy. For me, the problem isn’t that they are too easy, but that they waste the player’s time repetitively. (e.g., if you got all the moons, you spent 72 minutes waiting for the “You got a moon!” animation alone.)

It’s pretty obvious that Nintendo opted to favor mechanic-based challenge layering for difficulty rather than objective-based. I think this was a conscious decision: 1. Add a bunch of easy moons so that anyone can play. 2. Keep the hard moons few and far between so low-skilled players don’t get frustrated. 3. Use mechanics and orderless goals to encourage speed running. There is room for improvement in this design.

In future games, I would like to see harder challenges hidden from low-skilled players in places only high-skilled players could find (lenticular design). I would also like moons unlocked after a player beats the game to never be dead simple challenges. It seems like a waste of time to make a player who already finished the game find a moon from a cube that is sitting out in the open in a trivial place to get.

Conclusion

Mario Odyssey gives players the choice of what order to complete challenges. This choice enables more players to be engaged in the gameplay, both low-skilled and high-skilled. While the unordered nature also makes it hard for game designers to create side-moons with appropriate difficulty, Nintendo balances this with compelling, well-structured primary objectives. The blend of linear and non-linear challenges is what makes Mario Odyssey outstanding.